It’s 1783. Catherine the Great annexes the Crimea. A volcano in Iceland starts erupting and doesn’t stop for 8 months, killing thousands from famine and disease. A bunch of stuff happens in America but I’m tired of things being about America. An earthquake in Italy kills even more than the Icelandic volcano. Louis XVI was still the King of France, and ruled with his more-interesting queen, Marie Antoinette. Ten years later they would both be executed, but in 1783, Marie Antoinette was still the queen and she had recently appointed her favourite, the Duchesse de Polignac, as governess to her children. Bear with me, this is only vaguely about the royals.

Away from the wars, revolutions, natural disasters, and the French court, brothers Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier were working in the family business of paper-making in southeastern France. Étienne, the younger brother, was the sensible, business-minded one. Joseph was the dreamer; the creator.

The idea of building a flying machine came to Joseph in 1782 when he watched laundry drying over a fire. The heat from the fire formed pockets in the clothes as they billowed upwards. His first experiment in harnessing what he called the property of levity was a roughly one-metre square box-like chamber made out of thin wood, covered in a light taffeta cloth. When he lit some paper underneath the box, it lifted so effectively it crashed into the ceiling.

Joseph recruited his brother Étienne to this invention, and the two men eventually built a globe shaped aircraft, similar to the hot air balloons we know today, out of taffeta with layers of paper (handy being in the paper-making business). In the summer of 1783 they launched their globe in their home town of Annonay, where you can take commemorative hot air balloon flights to this day. Étienne went to Paris to make more demonstrations and also to establish their claim to this invention of flight.

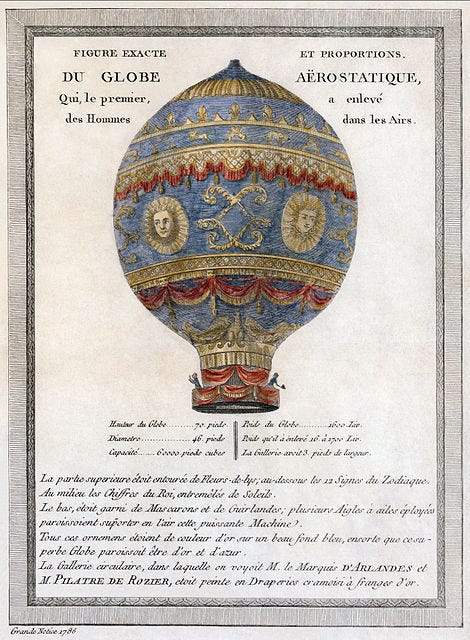

Despite being the original inventor, Joseph stayed behind in Annonay, as Étienne was the more suave marketing bro. Étienne enlisted the help of a wallpaper manufacturer, Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, and they constructed a huge envelope made of taffeta with a varnish of alum for fireproofing. The balloon was described as ‘sky blue, decorated with golden flourishes, signs of the zodiac, and suns’, which brings to mind that ubiquitous sun and moon bedding of the ‘90s.

The first flight that bore living creatures was in September. A sheep, because its physiology was considered close to a human’s, a duck because it can fly anyway and so should be fine with the altitude, so any ill effects would be attributed to the balloon itself, and a rooster, as a further control, because it was a bird but didn’t fly as high as a duck. The craft landed safely and all the animals survived, so it was time to send humans up.

King Louis wanted to send two condemned criminals up on the flight, because of course he did. When you’re the king, convicts barely count as people. Can you imagine being a prisoner in the 18th century, destined for death or an inevitably shortened life of hard labour and deprivation, and getting the opportunity to fly in a hot air balloon? Nervewracking, sure. But also magical. It seems impossible to me that you wouldn’t be overcome with awe and wonder while you’re in a hot air balloon. And if you didn’t survive? What a way to go. You’re doomed anyway, so why not be an aviation pioneer and witness something no one else had ever seen before? Why not.

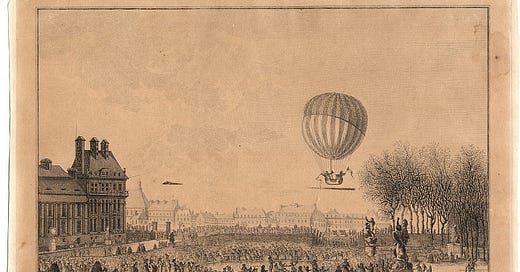

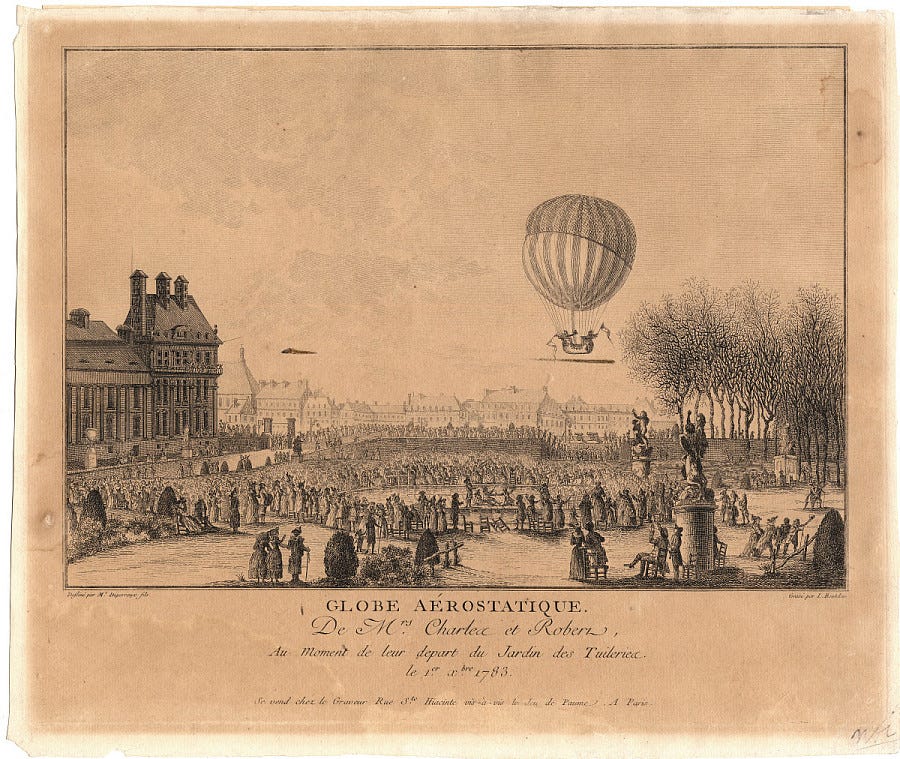

But King Louis was talked out of it. A science teacher named Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier pulled strings with the Duchesse de Polignac (remember her from paragraph one) and convinced the king that flying was too great an honour for convicts to do it, so Jean-François and a soldier named François Laurent d'Arlandes (also a marquis, which is the rank below prince and duke) got to do it. The marquis knew Joseph Montgolfier but Joseph wasn’t in Paris anyway because he was a hot mess, so who knows why François Laurent was chosen to go with Jean-François.

François Laurent d'Arlandes was later dismissed from the army for cowardice in the French Revolution, which makes sense. Why would a high ranked nobleman really want to overthrow the ruling system that he benefited from? I’m betting his heart just wasn’t in the whole revolution thing.

Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier died in 1785 in a balloon crash. He tried to cross the English Channel in a combination hydrogen and hot air balloon. They barely left France before the balloon was blown back over land and caught fire midair. His pioneering design became his legacy - our modern hybrid gas and hot air balloons are called the Rozière balloon. There is a whole list on Wikipedia of people who died using their own inventions, which seems fitting, somehow.

Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier lived to the ages of 69 and 55, respectively. They did some other stuff with their lives which isn’t terribly interesting. The French word for hot air balloon is montgolfière.

The duck and rooster and sheep probably got eaten.

In case the sub-heading seems odd, it’s from this song: